Understanding different Types of Multilinguals

Multilinguals are not all the same.

Most studies focus on successive and compound bi/multilinguals, assuming their “languages are all present at all times”. This misconception leads to an overgeneralization that is as misleading as the assumption that “multilinguals are multiple monolinguals in one”.

The way we acquire and organize languages varies significantly, depending on the individual contexts and learning experiences.

Understanding the distinctions between compound, coordinate, and subordinate multilingualism helps us better support language development of multilinguals in families and educational settings.

These terms were introduced by Uriel Weinreich already in 1953, and they provide very important insights into how bilinguals/multilinguals process and use their languages.

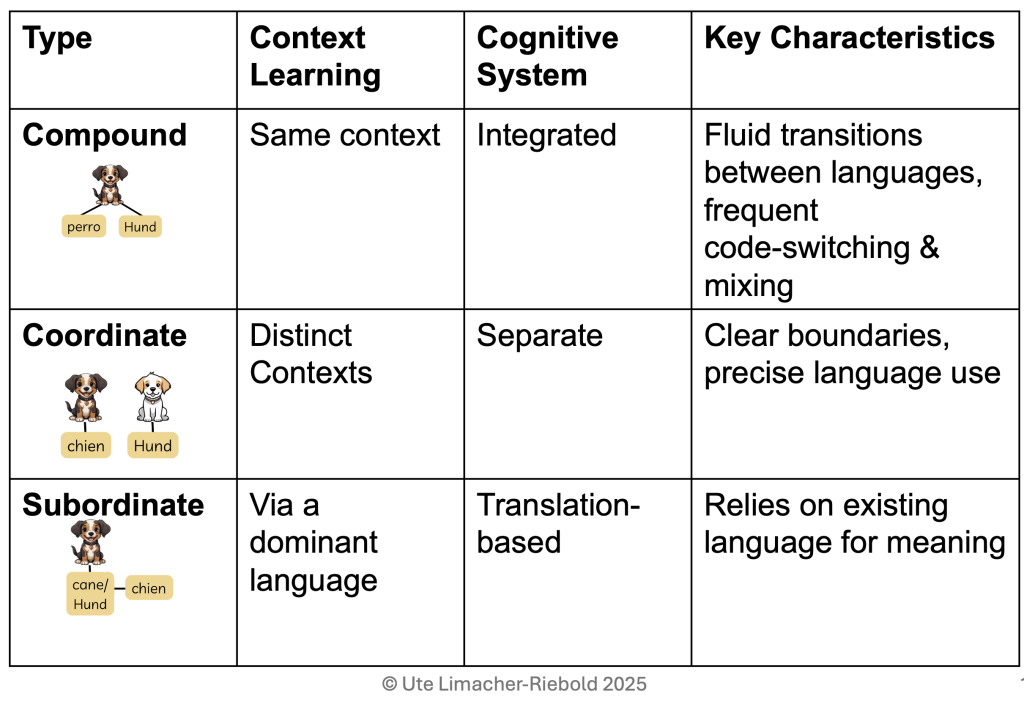

Compound Multilinguals

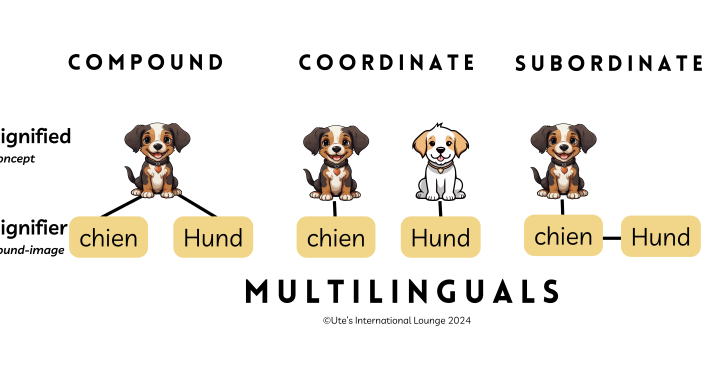

Compound multilinguals acquire two or more languages in the same context, associating both languages with the same concepts. For example, a child exposed to French and German at home from birth might connect both chien and Hund to the same mental image of a dog.

This results in an integrated cognitive system, where languages are closely interwoven. According to Grosjean (1982), compound multilinguals often engage in code-switching and code-mixing, effortlessly drawing on resources from both languages to express themselves.

Example:

A child whose parents use two languages interchangeably during everyday conversations develops compound multilingualism, associating ideas, emotions, and experiences with both languages.

Why is it important?

- Compound multilinguals tend to have native-like pronunciation and deep cultural insights into both languages.

- They benefit from enhanced cognitive flexibility, as navigating multiple languages fosters problem-solving skills and executive function.

Coordinate Multilinguals

Coordinate multilinguals acquire their languages in distinct settings, creating separate mental systems for each language. For instance, a child might speak Polish at home and use English exclusively at school, associating each language with a specific domain of life.

This separation allows for clear boundaries between languages, which can reduce interference and facilitate context-specific language use (Hamers & Blanc, 2000).

Example:

A teenager raised in a bilingual environment may use French exclusively with family members and German for academic purposes, keeping the two languages distinct in their mind.

Why is it important?

- Coordinate multilinguals often develop strong precision in language use, as they associate each language with specific contexts.

- This distinction supports academic success, especially in settings where multilingual proficiency is essential.

Subordinate Multilinguals

Subordinate multilinguals learn a new language by relying on their dominant language for understanding and expression. Instead of linking the new language directly to concepts, they use translation as a bridge. This type of multilingualism is common in classroom settings or when a language is learned later in life.

While subordinate multilingualism is often an initial phase, with practice and immersion, learners can transition to a more balanced form of multilingualism, leading to coordinate multilingualism.

Example:

A 10 year old child learning English through Italian translations — equating gatto with “cat” rather than directly associating it with the concept of a cat.

Why is it important?

- Subordinate multilinguals may initially struggle with fluency, but translation can serve as a helpful scaffold for learning.

- Structured exposure and immersion can accelerate fluency and help learners develop direct associations with the new language.

Comparison of Multilingual Types: