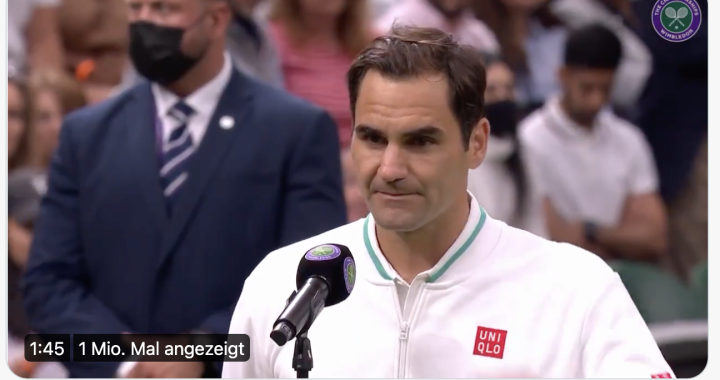

When I saw this interview with Roger Federer the other day, I couldn't resist but share it in my facebook group Multilingual Families.

It is a perfect example for why, when we use our language in international settings, we shouldn't assume that sayings, metaphors (and abbreviations!) are universal.

It's almost as if Roger Federer has a

British sense of humour! ??? #Wimbledon pic.twitter.com/wILm6SEfs1

— The Field (@thefield_in) June 29, 2021

In this particular example, Roger Federer made it very clear that "his mind went blank" when the journalist asked him if " (his) absence (on Centre Court) made the heart grow fonder (to come back, playing at Wimbledon)" applied to him too.

Let's have a look at the interview:

Journalist: "...is it true what they say that absence (is) making the heart grow fonder, being back here?"

Roger Federer: "I, I... sorry I didn't understand it." (look at his smile, he puts the arms behind his back, smiles to the public) "I heard that something absence, then, I don't know... my mind went blank-"

Journalist (smiles and repeats slightly louder): "I..Is it true they say about absence making the heart grow fonder and being back on Centre Court?"

Roger Federer (still his arms behind his back, shakes his head, looks into the public...): "I don't understand that saying..." (laughs and the public laughs with him; he looks at the interviewer) "My English is not good enough" (continues smiling and laughing...)

Journalist: "Fair enough... So, basically, having missed out last year [Federer: "Yes..."] away from this place for two years, how special is it to be back here?"

Roger Federer: (nods, puts the arms in front of him again) "Yes, there you go (public laughs, then claps, Federer crosses the arms in front of him, touches his face and waits until the public calms down) A good reminder my English is not very good but it's ah... (Journalist: "It's better than mine!") no, no no... Ah, no, look, ah... I think we're all very happy, all the players, I think including all the fans and the organizers and everybody... that we get a chance to black ah... playing again back on tour overall. Especially here in Wimbledon and plus with the crowd, it would have been the worst to have this term with no fans. This would have been ... absolute killer... (cheering from the public) but it's ah...(applause and cheering from the public). That's... it's... it's such a privilege to play here. (puts his arms again on his back) Look, I couldn't be more excited. I made it after a long hard road last year and so forth, but ah... I'm happy I get a chance for a second match and I'll see how it goes, but I hope everybody else is having a great time (puts his hand up on the side) but even though it's raining but that's normal so (puts his arms on his back again, smiles, nods and talks to the public; the public is cheering) I'll see you at the second round".

This kind of mis-communications happen all the time in international settings (and not only in international settings) for the simple reason that we usually assume that the way we express ourselves is "clear enough", that the other person will understand what we mean and how we mean it. I like to quote Karl Popper: "It is impossible to speak in such a way that you cannot be misunderstood". The same applies to the receiver: you can not assume that you'll understand everything the other person says. Not because you are not "good enough", "fluent enough" (whatever that means!!) in the language, but because the context, the word choice and the intonation, articulation, the use of sayings, metaphors etc. usually allows multiple interpretations and can be misleading.

In this particular situation, the interviewer could have explained what he meant immediately, without putting Federer on the spot. He could have rephrased it, paraphrased it, made an example... But he assumed that Federer "zoomed out" for other reasons – like acoustics, short distraction or because he was tired – and repeated exactly the same question.

Now, in this kind of situation we all know that some people would just ignore, do as if they understood something else and answer whatever they want to share, without letting the other person know that they didn't understand.

It requires a high sense of loyalty towards the interviewer and self confidence to react the way Roger Federer did. His English is very good and the way he reacted was top. After saying that he didn't know the saying he added "my English is not so good" – like an excuse. For this last comment or self-judgment people on twitter said that "he might have British humor after all". I think it has more to do with Federer being used to international settings and not taking this kind of situation too seriously, not personally. Federer is perfectly able to laugh at himself – a skill that comes with being multilingual and multi-cultural.

It is always ok to ask for clarification, no matter if in a private conversation or, like here, in front of a big public and when we're put on the spot. Roger Federer, who is perfectly capable of adjusting to the British communication patterns, gave the journalist the chance to reformulate the question by saying overtly what happened: his mind went blank which means: "something triggered my mind to go blank, aka, I didn't understand what you just said...".

This is a very polite and indirect way to signalize that one needs clarification. People who are used to "reading the air" or "reading in between the lines" would have reacted accordingly, without putting him on the spot. But in this particular situation, the journalist assumed that this meant that Federer didn't "hear" him (acoustically). He took it at face value, i.e. that Federer really didn't hear what he just asked, and chose to repeat the question. Let's not forget the situation: the journalist knew how fluent Federer is in English and didn't assume that he wouldn't be familiar with the saying and, he most probably expected a more direct hint.

Federer realized that the journalist didn't understand and specified why his "mind went blank" by adding that he didn't understand that saying.

Now, one can be quick at judging the journalist and saying that he didn't manage to understand what went wrong. But when Roger Federer said that he didn't know the saying and that his English wasn't "good enough", the journalist replied that "it's better than mine".

I think most people who listened to this interview didn't understand what the journalist wanted to point out here: he realized that he didn't manage to adjust his language in this interviewee, and caused what could have been a very embarrassing situation for Roger Federer. He apologized in his own way. He emphasized with Federer's situation and quickly positioned himself and his English "under" the level of comprehension of his interviewee, which, in my opinion, saved the situation.

When the journalist explains what he means, Federer says "there you go", triggering the public to cheer, and relaxing the situation that could have been quite embarrassing. By responding in this colloquial way, Federer showed his flexibility and capacity to steer the interview back to where it was.

You can tell that I am a fan of Roger Federer – not only because he is Swiss! – but that's not the reason I chose this example. I think we should always look at both participants in a conversation: how are they adjusting to the other's way of communicating?

I train internationals and those who work with internationals, become internationally fluent or multi-competent in international settings.

There are very effective strategies one can learn to master this kind of situation with dignity, without loosing the face, self respect and the trust of the other person, exactly how Roger Federer and the journalist did in this example.

In every conversation – and interviews are conversations! – both interlocutors need to adjust their "communication game" to the situation. I like to compare turns in a communication to a tennis game, where you want to have "many successful turns" (without dropping the ball...) and where the pass to the other player can trigger some new reaction, a new way of playing/communicating that you may not have explored yet, but that makes it fun and entertaining. Like every effective communication we want it to be enjoyable and to have a positive outcome for everyone involved.

My questions for you:

- Does it happen to you that in one or more of your languages you don‘t get certain meanings/allusions etc?

- How do you respond? Do you feel inadequate, or blame yourself?

- Do you adjust your language to your interlocutor? If so, by doing what exactly?

Please let me know in the comments.