Bilingualism, Multilingualism and Plurilingualism

Bilingualism has long been a subject of linguistic and cognitive inquiry, evolving from strict early definitions to more fluid and inclusive conceptualizations. It has been reflecting different research paradigms, cultural contexts and social attitudes toward language use.

Early definitions emphasized fluency and equal competence in two languages, whilst more recent approaches recognize the spectrum of abilities and functions, reflecting broader changes in our understanding of language use, cognition, and identity.

Bilingualism, Multilingualism and Plurilingualism – in a nutshell

The term bilingualism traditionally referred to individuals using two languages, while mulitlingualism described the coexistence of multiple languages side-by-side in a society but are utilized separately. For example, in Switzerland, four national languages and numerous dialects coexist within distinct domains. More recently, multilingualism has also been applied to smaller social units, such as families, who actively use multiple languages or dialects (Hamers & Blanc, 2000).

The term plurilingualism was introduced to distinguish individual linguistic competence from societal multilingualism. While Denison (1970) initially discussed multilingual contexts involving multiple languages, the concept of plurilingualism evolved to focus on the individual as an active agent in managing and integrating their linguistic repertoire. Coste, More and Zarate (1997) further emphasized that plurilingualism represents the dynamic interplay of languages within a speaker’s communicative practices, contrasting with multilingualism’s focus on societal language coexistence. This theoretical shift underscored that languages within an individual’s repertoire are interconnected rather than compartmentalized.

The Council of Europe (1997) formalized plurilingualism to highlight the agency of individuals in leveraging multiple languages for communication across various contexts. This term has since gained prominence, particularly in French discourse, where it is commonly used to describe individuals with diverse linguistic repertoires.

In this post, I use bilingualism, multilingualism, plurilingualism to refer to individuals who navigate multiple languages, dialects, or sign languages, while acknowledging the distinct theoretical nuances outlined by Denison (1970), Hamers & Blanc (2000), and Coste et al. (1997).

Early Definitions: Bilingualism as Native-Like Mastery

At the beginning of the 20th century, one of the earliest and most rigid definitions came from Bloomfield (1933), who described bilingualism as “native-like control of two languages”.

His perspective also implied that bilinguals must acquire both languages early and with “full proficiency”, mirroring monolingual competence in each language.

This narrow perspective assumes that bilingual individuals must not only acquire and learn both languages from early on (before age 3), but also exhibit equal proficiency in both languages across all domains. However, such a definition excluded many individuals who learned additional languages later, and those who actively use multiple languages in their daily lives without achieving native-like competence in all of them.

A More Inclusive Perspective: Degrees of Bilingualism

Haugen (1953) challenged Bloomfield’s view by proposing that bilingualism exists on a continuum. Instead of requiring native-like proficiency, he suggested that bilingualism begins when a speaker can produce meaningful utterances in another language.

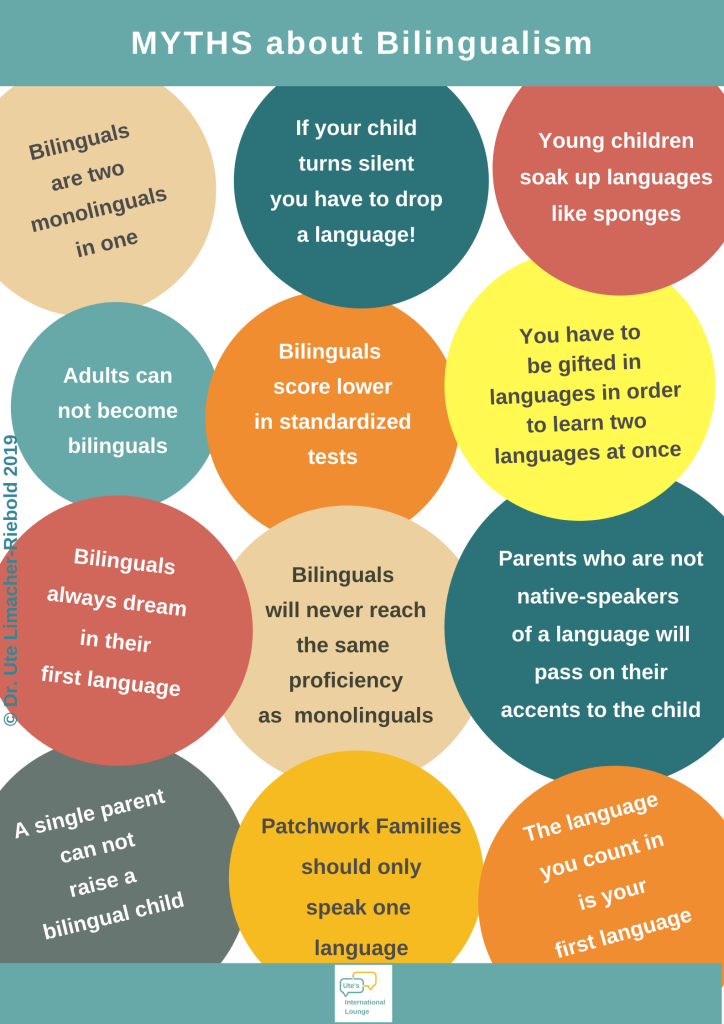

This view assumes that bilinguals must possess perfect (!) fluency in both languages, like “two monolinguals in one”. This rather rigid definition excluded the majority of real-life bilinguals who use their languages in a variety of contexts, for specific purposes and to various extent.

Diebold (1961) introduced the concept of incipient bilingualism, referring to the earliest stages of bilingual development (or “the initial stages of contact between two languages”). This helped frame bilingualism as a process rather than an all-or-nothing phenomenon.

Bilingualism as a Functional and Social Phenomenon

As the early definitions of bilingualism set rather unrealistic expectations, researchers began to adopt a more practical approach.

Weinreich (1953) categorized bilinguals into “coordinate”, “compound”, and “subordinate” types, depending on how their linguistic systems interact.

Mackey (1970) considered bilingualism as the “alternate use of two or more languages by the same individual”, and focused on the use of the languages rather than equal proficiency. Following the need to examine bilingualism along multiple dimensions, including proficiency, function, and stability, he argued that bilingualism is not a static state but a dynamic process shaped by social and individual factors.

Macnamara (1967) introduced the idea that even individuals with minimal proficiency in a second language should be considered bilingual if they can use it functionally. A minimal competence in only one of the four language skills – listening, speaking, reading and writing – in a language other than the mother tongue was necessary.

This perspective paved the way for recognizing partial and receptive bilinguals – those who understand but may not actively or verbally produce a second language.

Bilingualism as a Dynamic Continuum

Weinreich (1953) defined bilingualism as “the practice of alternately using two languages”, laying the foundation for later scholars like Grosjean (1982), who challenged the traditional notion of bilinguals as two monolinguals in one person. Instead, bilingualism is best understood as a fluid, context-dependent process where individuals integrate both languages into their cognitive and communicative repertoire. This holistic perspective recognizes code-switching and code-mixing as natural and strategic bilingual behaviours, rather than signs of confusion or deficiency.

Bilingualism in Society and Individual Identity

Romaine (2019) and Wei (2020) emphasize that bilingualism is not merely an individual trait but a societal and interactive phenomenon. Multilingual societies shape how individuals navigate their linguistic environments, influencing identity and communication.

Grosjean (1985, 2010) further dismantled the “fractional view” of bilingualism – the idea that bilinguals should mirror monolingual proficiency in each language. Instead, his complementary principle highlights that bilinguals use their languages in different domains, and for different purposes, making the notion of perfectly “balanced” bilingualism both unrealistic and unnecessary.

Contemporary Understandings of Bilingualism

Bilingualism is not merely an individual skill but is deeply embedded in education, policy, and identity (Baker, 2001; Baker & Wright, 2017). Using more than one language on a regular basis, rather than being an exception, is the global norm for over half of the world’s population. Individuals and communities navigate multiple languages seamlessly, challenging rigid distinctions between bilingual and monolingual speakers. In the digital age, concepts like translanguaging (Wei, 2020) emphasize how multilinguals dynamically draw from their full linguistic repertoire, reshaping traditional views of communication.

This dynamic interplay of languages occurs on both individual and societal levels. Societal bilingualism refers to entire communities functioning bilingually, while individual bilingualism focuses on a person’s use of multiple languages (Baker & Wright, 2017). The distinction mirrors that between bilingualism and multilingualism, with the former often describing an individual’s proficiency in two or more languages, while the latter refers to societal contexts where multiple languages coexist. Context – whether in family, education, or community – plays a crucial role in shaping bilingual experiences.

To further categorize these settings, researchers distinguish between micro-, meso- and macro-societies. Micro-societies, such as families or close-knit communities, shape language practices through personal relationships. Meso-societies, including schools and workplaces, mediate language policies and practices between individuals and broader societal structures. Macro-societies operate at national or global levels, reflecting overarching language ideologies, policies, and sociolinguistic trends.

These layers reveal how multilingual experiences are shaped by their environments, reinforcing the need for a contextualized understanding of bilingualism. As we all use different languages depending on the setting or context, I tend to prefer the use of “multilingual” person or “multilingualism” whenever more than two languages are involved. Hence, the name of this website.

The Use of Multiple Languages in Family and Society

In multilingual families, the use of multiple languages takes on diverse forms, shaped by strategies such as Minority Language at Home (mLAH), One Person One Language (OPOL), Time and Place, Two Persons Two Languages, or a flexible mix of approaches. The goal is not necessarily to achieve “native-like” proficiency but to foster meaningful communication, identity, and intergenerational connection. Language use in family settings is dynamic, adapting to shifting circumstances, relationships and social needs.

Defining who is bilingual or multilingual or plurilingual (whatever term you prefer) remains a challenge. As Baker (2001) notes, proficiency cannot be reduced to rigid benchmarks in listening, speaking, reading, or writing. Instead, the bilingualism/ multilingualism/ plurilingualism should be understood in terms of function – how individuals use their languages in real-life contexts. A person who understands a language but does not speak it, or who can read and write but struggles in conversation, is still engaging in bilingual practices. In languages without standardized written forms, spoken fluency alone may define competence. The complexity of multilingual abilities highlights the limitations of traditional proficiency-based definitions.

Baker (2001, 5) illustrates this fluidity:

The four basic language abilities do not exist in black and white terms. Between black and white are not only many shades of gray; there also exist a wide variety of colors. The multi-colored landscape of bilingual abilities suggests that each language ability can be more or less developed.

This “multi-colored landscape” of bi-/multilingualism reflects the variation in language skills, from basic comprehension to nuanced fluency, and from informal conversational abilities to academic or professional expertise.

Sub-skills such as pronunciation, vocabulary depth, and grammatical accuracy further complicate the picture. Importantly, formal language assessments often fail to capture the social and practical dimensions of multilingual competence, overlooking skills essential for real-world interactions.

Rather than a binary state, multilingualism is a fluid and dynamic spectrum, shaped by individual experiences, societal contexts and communicative needs. It emerges from extensive contact between languages, manifesting at national, community and personal levels. As Wei (2006) emphasizes, bilingualism lies at the core of modern linguistics, raising fundamental questions about language acquisition, use, and the human capacity for multilingual communication. Recognizing its complexity allows us to better support bilingual individuals, families, and communities in meaningful and effective ways.

Bilingualism is a product of extensive contact between people speaking different languages; it manifests both at the national and community level and at the individual level. Bilingualism as a research topic is at the heart of modern linguistics, raising fundamental theoretical issues of the human language faculty, language acquisition and language use. (Wei, 2006)

Conclusion

Our understanding of bilingualism has evolved from Bloomfield’s rigid definition to a more dynamic, socially embedded perspective. Like multilingualism and plurilingualism, it is no longer seen as a fixed category, but recognized as a fluid and functional reality, shaped by individual experiences, societal structures, and communicative needs. Rather than measuring proficiency through rigid benchmarks, contemporary research emphasizes how languages are used in real-world contexts – whether within families, schools, workplaces, or broader societal settings.

As translanguaging (Wei, 2020) demonstrates, individuals who regularly use several languages, seamlessly draw from their full linguistic repertoire, challenging traditional distinctions between monolingual and bilingual speakers. Likewise, the recognition of micro-, meso-, and macro-societal influences (Baker & Wright, 2017) highlights the contextual nature of bilingualism, showing that language use is deeply embedded in relationships, policies, and ideologies. The “multi-colored landscape” of bilingual abilities (Baker, 2001) further reinforces that bilingualism is not a binary state but a dynamic spectrum, where different skills develop and manifest in varying ways.

As societies and communication in multilingual settings continue to evolve, so too will our understanding of bilingualism. Acknowledging its complexity allows us to normalize multilingual individuals, families and communities, whose language practices should not only be valued for their proficiency but also for their role in identity, connection and social interaction.

Multilingualism is a dynamic spectrum where different skills develop and manifest in varying ways.

Looking Ahead: Real Stories from Multilingual Families

While this first part focuses on the evolving definitions and theoretical understandings of bilingualism (multilingualism and plurilingualism), Part 2 will shift from theory to lived experience, bringing to light the voices behind the concepts – parents, children, and educators navigating life in more than one language.

From joyful discoveries to everyday challenges, these personal stories will reveal the many shades of what it means to grow up and raise multilingual children abroad.

Stay tuned!

References:

Baker, C. (2001). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Multilingual Matters.

Baker, C., & Wright, W. E. (2017). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism (6th ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Bloomfield, L. (1933). Language. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Coste, D., Moore, D., & Zarate, G. (1997). Plurilingual and Pluricultural Competence. Council of Europe.

Coste, D., Moore, D., Zarate, G. (2009). “Plurilingual and Pluricultural Competence”. Council of Europe.

Council of Europe. (1997). Modern Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. A Common European Framework of Reference.

Denison, N. (1970). “Sociolinguistic Aspects of Plurilingualism”. Social Science. 45 (2): 98-101.

Diebold, A. R. (1961). “Incipient Bilingualism.” Language, 37(1), 97-112.

Grosjean, F. (1982). Life with Two Languages: An Introduction to Bilingualism, HUP.

Grosjean, F. (1985). “The bilingual as a competent but specific speaker-hearer.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 6(6), 467-477.

Grosjean, F. (2010). Bilingual: Life and Reality. Harvard University Press.

Haugen, E. (1953). “The Norwegian language in America: A study in bilingual behavior.” Publication of the American Institute, 1, 88-92.

Hamers, J.F., Blanc, M.H.A. (2000). Bilinguality and Bilingualism. 2nd ed., CUP.

Macnamara, J. (1967). “The bilingual’s linguistic performance – a psychological overview.” Journal of Social Issues, 23(2), 58-77.

Mackey, W.F. (1962). The Description of Bilingualism. Canadian Journal of Linguistics, 7(2), 51-85.

Romaine, S. (2019). Bilingualism. 2nd edition. Blackwell.

Wei, L. (2006). Bilingualism, Ed. Keith Brown, Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics (Second Edition), Elsevier, 1-12.

Wei, L. (2020). Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language. Routledge.

Weinreich, U. (1953). Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. Mouton.