Many internationals end up talking another language with their child than the one they chose at the beginning.

There are different reasons for this:

– They live in a country where their mother tongue is not recognized as an important (= prestigious enough...) language, i.e. it is not supported by the school and society, and there is not a linguistic community which could help to support these families to keep on talking this language – at least in private.

– They don't consider their family language important enough to pass it on to their children – because they don't have family and friends who share this language, and are second or third generation speakers themselves.

– Doctors and teachers told them to drop their family language in order to help their children integrate easier into the local school and perform better.

This last reason is, alas, the most common one. In many countries, schools and societies are getting more and more aware of the importance to maintain the heritage languages, since research clearly proves the benefits of it on the childrens' academical performances on the long run.

But what about the other two? – When a language is considered "not important enough" by a society (and, consequently, by schools, teachers, doctors, locals...), and there are no resources available for these families to foster the language in a spontaneous and natural way – communities, libraries, language learning opportunities etc. – it is almost impossible for parents to maintain a language "alive" in their family.

If they manage despite these difficult circumstances, the language becomes tendentially "artificial". In order to keep a language "alive", it needs to be practiced on different levels: to become fluent and confident in a language one needs to be able to distinguish between several registers, understand slang for example and a broader range of meanings.

This situation becomes even more complex for bilingual parents: Which language should they choose to talk with their children? Do they need to choose or can they pass on both or all of their languages?

Linguists usually recommend to speak the “mother-tongue(s)” (i.e. the parents' language(s), the family language(s)) to our children. But which is the mother-tongue if you are a balanced bilingual and if your extended family talks both or even more languages? – When it comes to agreeing on the languages to speak to our children when we, parents, are already bilinguals (= understand /talk /read /write two or more languages), there is not one-size-fits-all solution.

My personal experience...

I am a multilingual parent and grew up with 2 languages myself (Italian and German). We were living in Italy when our son was born and as Italian is one of my dominant languages and actually the one I'm most spontaneous in, it was natural for me to speak Italian to him from the beginning.

Our home languages were Italian (me and my son), Swiss German (my husband and my son) and German (my husband and I) and we knew that he would pick up German automatically too.

When we moved to the Netherlands our son was 2,5 years old. Two months after he started attending a Dutch daycare, he stoped responding in Italian to me.

My husband was still speaking Swiss German to him and I noticed that my son preferred to answer me in Swiss German or even Dutch. Nevertheless, I kept on speaking Italian, assuming that this was just a phase.

When children are exposed to another language in a "full immersion" way, like it was at the daycare for my son, they tend to prefer that language to the other languages (cfr. the "home-" or "family-languages") and once they feel more comfortable in both (or more languages), and the input in all languages is still enough and there is a proper need for them to speak all the languages, they get back at speaking them all. – So I persisted with Italian, knowing that he would at least gain a passive competence in this language.

Unfortunately in this period we didn’t find Italian families with children of his age and I was the only person he would speak Italian with. Also, he realized that I understand and talk the other languages too: I learned Dutch with him and perfectly speak Swiss German and German too.

So, all he was doing was following the economic principle in languages: he didn't see why he should keep on speaking Italian with me, there was no real need for him to do so.

The concept of economy – a tenet or tendency shared by all living organisms – may be referred to as "the principle of least effort", which consists in tending towards the minimum amount of effort that is necessary to achieve the maximum result, so that nothing is wasted. Besides being a biological principle, this principle operates in linguistic behaviour as well, at the very core of linguistic evolution. In modern times it was given a first consistent definition by André Martinet, who studied and analysed the principle of economy in linguistics, testing its manifold applications in both phonology and syntax.(Alessandra Vicentini, The Economy Principle in Language, 2003)

I still kept speaking Italian to my son and to my twin daughters who were born a year after we arrived to the Netherlands, confident that when they would start speaking Italian, my son would follow them and everything would be fine.

In fact, all three spoke Italian to me for almost four months when my daughters were 11-15 months old : my daughters started forming monosyllables around month 10/11 in Swiss German, Italian and Dutch).

When plans change...

But then, my daughters started to communicate in an autonomous language that had nothing in common – neither phonetically, nor morphologically – with the languages they were exposed to.

This secret language became a problem in our family because nobody could understand what they were saying. It was mainly because our son was suffering from this situation – he couldn't understand his sisters and we weren't able to "translate" the meaning of the words they used either – that we decided to choose German as our family language. I was fully aware of the problems that could arise – confusion, subtractive bilingualism, language refusal from all children, loss of emotional bond if my husband and I would cease speaking Swiss German, respectively Italian with our children, only to name a few... – and this would surely not be something I'd advise parents to do! But to avoid that my son would feel excluded and that his level of anxiety would worsen, and for the sake of a healthy linguistic atmosphere in our multilingual home, we decided to give it a try. It was very important for me to include our son in the decision making process! I am a firm believer, and research confirms this, that children's agency, their active involvement in this kind of situations is of great importance!

Cummins draws the distinction between additive bilingualism in which the first language continues to be developed and the first culture to be valued while the second language is added; and subtractive bilingualism in which the second language is added at the expense of the first language and culture, which diminish as a consequence. Cummins (1994) quotes research which suggests students working in an additive bilingual environment succeed to a greater extent than those whose first language and culture are devalued by their schools and by the wider society.

We did not completely stop speaking Swiss German and Italian at home. We shifted the focus on German, but maintained the other two languages in one on one settings and when reading and singing with our children, and, of course, when speaking with our Swiss German and Italian speaking members of the family. I was constantly monitoring my children's reaction and behaviour.

Luckily our children responded very well to this change: after two months our daughters completely stopped speaking the secret language and started speaking German and our son showed a very positive reaction to us speaking German all together. They increasingly searched to communicate with us in German and would also enjoy listening to the other languages. We agreed that their Italian and Swiss German would, for the moment, rather be passive (receptive multilingualism), knowing that understanding our languages would make it easier later on to activate the languages and become verbal.

It is important to add that our daughters started going to a Dutch daycare 1, later 2, then 3 days a week, starting from 7 months. They were in separate groups with the possibility to meet over the day and play together if they wanted. The reason for this early socialization was that I observed them assuming a clear behaviour of giver and taker, which I first tried to balance with playdates. Arranging regular gatherings with other parents of infants was not possible and I saw that it didn't work as my daughters would rather prefer playing with each other than with other children. My intent was to make them experience play and interaction with other children of the same age, to learn socialise with others and find their very own way of being and interacting. I know that many twins can't stay apart, or suffer when they don't see or hear their twin. My daughters were different from the beginning. They would search physical contact when napping or during the night, but not so during the day. They enjoyed discovering the world each in her very own specific way. – The development of this autonomous language, also known as cryptophasia, came "out of the blue" and both were already verbal in our languages. I know that some twins or siblings develop this secret language at different times in life, but what I didn't know was how long it would take until this phase is over. I didn't want to risk the health of my son and the bond we have as a family, that was compromised by this isolating language...

More than 10 years later...

More than 10 years later, my children speak English, Dutch and German on a daily basis, they also speak French and Spanish on a basic level, and our son is learning Chinese. They all understand and speak Italian on a A1/A2 level, and Swiss German. In order to support Swiss German and Italian we used to spend our summer holidays in Switzerland, meeting family and friends who would provide the necessary input during our stay. We stoped with these language immersion holidays three years ago, because we decided all together to focus on the languages we need in our daily life: German, Dutch and English.

I observe that all three have very different preferences when it comes to languages, and I am happy to see that they don't refuse any of them. They have attained different levels of fluency, and that is enough for what they need right now. Should they ever need to improve any of their less dominant languages at some point, I know we have planted the seeds. We have watered the plants regularly, some more than others, but that's how it goes. We can't expect to be perfectly balanced in all our languages, that isa huge myth many parents want to make true. What I'm sure though is that they all are aware of the gift of languages they have, they are proud of it and they know what to do should they want to improve their language skills in any of them!

How we did it

For multilingual parents maintaining one or more minority languages* requires a considerable effort and is a greater commitment and challenge. Some families follow the Time and Place strategy, ie. they have fix situations and times where they talk one or the other language. – I usually recommend this strategy with older children who have already a sense of time and understand why a parent would switch to another language. In our family we have agreed on times when we speak English or Dutch at home: during the week, after school and when we have guests who don't speak German.

When my son was born we thought he would become fluent in Italian and German – attending a school in Italy – but when we moved to the Netherlands we had to reassess our language situation. He went to a Dutch daycare and we thought he would attend a Dutch school later; so Dutch became the dominant language for a year. When we decided to send him to an English speaking school, this changed again: English, Dutch and at that time German, became his most dominant languages.

For our daughters, who started speaking Swiss German and Italian, Dutch and German were the most dominant languages until age 3 and English replaced the Dutch when they started attending the same school as their brother.

We never had long term language goals as we knew that all can change and would change, due to international moves and our children being schooled in their fifth language (chronologically speaking), and growing up in a highly multinational and multilingual community.

When my son asked me explicitly to restart speaking Italian with him more regularly because he noticed that when I was talking Italian with friends, I would remind him of earlier and he wanted to connect through this language with me, we agreed on a plan to speak Italian to each other during our one on one time.

Unfortunately our school doesn't provide sufficient language tuition and I gave my children language lessons in German for 2 years. Only 2 years because I noticed that it didn't work to be mum and teacher with my children. We agreed that they would watch German TV, listen to German podcasts and audiobooks, and read books in German.

In 2017, this was our situation:

"my daughters recently (May 2017) asked me to teach them Italian and I now dedicate 2 hours per week to "teaching" them Italian in a natural way – we read texts, do role plays, listen to music. As all three children have an analytical approach to Italian I introduce grammar (how you form plurals, according adjectives etc.) to them in a context based way, i.e. when we listen to a song or read a text I will focus on one aspect, for example the form and agreement of adjectives in Italian.

At the moment I dedicate 6 hours per week to teach my children German, Italian and French. – The goal that we have agreed on is for them to become nearly native in German (C2 level) and confident enough in Italian and French (both B2 or C1). "

In 2020, the situation is very different. I don't teach any language to my children anymore. They have made the commitment and took the responsibility to work on their language skills independently. Reading in German or Italian is not what they do spontaneously, or at least, it is not their first choice. Two of my children are book worms and I fully welcome this no matter the language. German is a language they find too difficult to read ("the sentences are so long... and so boring..."), so they tend to opt for shorter texts – posts, online articles, and whenever possible, prefer videos...

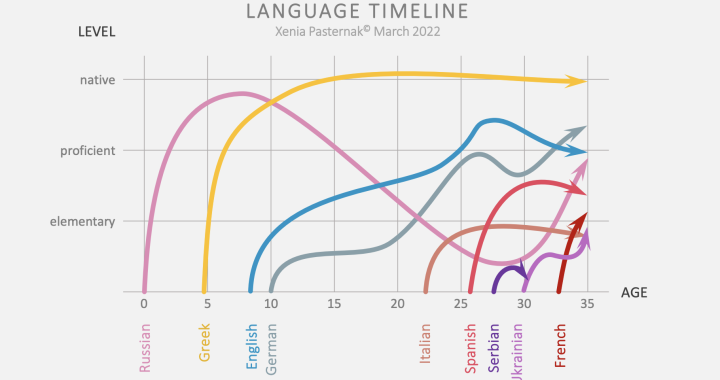

In 2024, all my children are adults and they have a native and nearly-native level in English, Dutch and German. They understand, speak, read and write Italian, Spanish and French to different levels of proficiency, and understand and speak also Swiss German. In the past 4 years my son has started learning Mandarin Chinese and Japanese independently, and keeps improving his French. One of my daughters is learning Russian, the other one Thai and Mandarin Chinese.

Never give up!

Many of my clients struggle with accepting that their children don't speak their language, that they don't respond in the family language. Not sharing their language with their children deeply affects them and many surrender.

One of my clients managed to talk Italian to his daughter for 10 years, not getting any response in Italian, only in Dutch or English. His daughter was perfectly able to understand Italian and would also speak basic Italian with extended family, but knowing that her father was fluent in English and Dutch. Growing up in a highly international environment where English and Dutch are the dominant languages, made her prefer these two languages even when speaking with her Italian father.

We all identify with the languages we know, with the cultures they represent and everything that we associate with the language. Not speaking a language we feel very connected with with our loved ones feels like missing out the opportunity to share the most spontaneous thoughts and emotions with them.

Speaking German with my children feels like speaking through a filter, whereas when I speak Italian, I speak from my soul: this is why I never gave up on Italian!

I always ask my clients: if you could fast forward 10 years, would you be happy not to speak your language with your child?

What about when you become grandparent? If you feel that you have to silence part of you by not speaking your language, that you don't feel comfortable with it in some way, then don't stop talking your language to your child, no matter how your child responds.*

The daughter of my client did the same as my son and my daughters: after several years she started talking Italian again. She had listened to his Italian for years and built a passive/receptive vocabulary, and knew exactly how to form sentences and is now (at age 18) nearly native!

* I must add that there are some extreme situations where I would not advise to keep talking your language to your child, but these are very extreme (for more information about this you can contact me anytime)

When the dominant language wins... again

Many internationals whose mother tongue or L1 is a minority language know how it feels like when their children prefer a more dominant language even at home. When they almost forget their family language(s) or consider it "not worth to be learned". – For parents this equals with a personal rejection from their children – although this is usually not the children's intention!

With my clients who are in this situation I do regular assessments to analyze their language situation, the way their children cope with it.

I consider this very important as we all, our situations and our language preferences change over time, and we should let all members of the family know what our expectations are and try to adjust and agree on which languages to maintain. (Ute)

As I mentioned before, we never had unrealistic language goals with our children, and I made sure that our children always had a say when it came to language choices!

We always have to look at the bigger picture and follow the long term goal which, for my family, is to keep on learning languages, stay flexible, and adjust to the different situations and needs. ~Ute's International Lounge @UtesIntLounge

Parents of bilingual children have to make choices that may not be the ones they wanted in the beginning, but that are necessary for their children to adapt to the situation they find themselves in.

I sometimes wonder: if the situation with my daughters wouldn’t have happened, my children would still speak Italian and Swiss German at home, and be less fluent in German. My children wouldn't be in the German native-speaker class at school – but among the Italian native-speakers. To be honest, it doesn't make a big difference for me, as German and Italian are my first languages, my two L1's. As for Swiss German: it is an oral language only, and therefore it was not difficult to accept that our children would learn it "on the side" – they understand everything today, and can also distinguish and understand different Swiss German dialects, which is, in my opinion, a fantastic achievement, considering that they spend on average 1 week in Switzerland per year!

When my son told me that he would like to speak Spanish and French at home too, I first got anxious because my children spend most of their time at school, have after school activities and homework to do, so the time to practice on those languages is not enough to foster these languages too. But it wasn't about reaching nearly native fluency! My son only wanted to exercise these languages with me, speak them and analyze them with me.

We agreed on the fluency he wants to achieve in all the languages he is learning and improving, and so far I am very pleased to see that he takes this with the right spirit: he enjoys speaking the languages he chose and make the best out of it. He has published a guidebook for students preparing for their GCSE and is currently learning Chinese and Japanese.

Heute we speak quasi ogni giorno alle taalen, pero no es importante qu'on les parle parfaitement: it's more important, Spaß dabei zu haben en ze alle heelemaal te genieten!

*minority language: a minority language is a language that is different from the official language(s) of a state and usually spoken by less than 50% of the population of a society/ community.

The term "bilingual" is here used to define people who understand and speak two or more language to a certain extent.

If you would like to know more about this and are interested in an assessment of your family language situation, contact me at info@UtesInternationalLounge.com – and have a look at my services here.

© Ute Limacher-Riebold, 2024

Related articles