What they are, why they happen, and how to prevent them

In multilingual families, multiple languages tend to be used on a more or less regular basis. When one (or more) languages are not used or used less for a longer period of time, it can lead to language shift. This means that one or some of our languages are then likely to move to the background (Limacher-Riebold, 2023).

Language shift, language attrition and language loss are processes that can deeply affect us, particularly when our heritage languages are at stake!

What are language shifts, attrition and loss?

Language shift occurs when either a community or an individual gradually moves from using one language to another.* This is often due to external pressures. For communities these can be migration, colonization, or globalization. For individuals, the community can pressure towards the use of more dominant languages, i.e. languages that are more important to function in the society – whether it be the community, nation or even the family. Over time, the dominant language replaces the minority or heritage language in daily communication.

Language Attrition refers to the gradual decline of proficiency of a language an individual once spoke fluently. This can happen with both, the heritage and any additional language learned at any point in life.

Language Loss is the extreme outcome of attrition, where a person or community no longer effectively uses a language, either entirely or in specific domains.

These processes are often intertwined, with language shift accelerating attrition and loss.

Why and when do these processes happen?

Language shift can happen at any stage due to a change in language use (see here above) and it is rather temporary, i.e. it can be reversed at any stage with some conscious effort to use the language more frequently.

Language attrition and loss are often the result of the “use it or lose it” principle grounded in neurolinguistics (Schmid & Köpke, 2004) over a longer period of time. When a language is not used regularly, neural pathways associated with it weaken, making it harder to retrieve vocabulary, syntax and pronunciation.

Common Triggers are:

Migration or Environmental Changes: Moving to a region where a different language dominates can limit opportunities to use the heritage/other language.

Educational and Work Demands: Prioritizing the dominant societal language for studies or career advancement often sidelines minority languages.

Family Dynamics: When family members adopt the dominant language for convenience or integration, the heritage/other language loses its functional role.

Limited Domains of Use: If a language is restricted to specific contexts (e.g., only spoken with grandparents), its active vocabulary and grammar can shrink.

Signs of Language Attrition

Language attrition can manifest in multiple ways and subtly over time. Here are some common indicators:

Word retrieval difficulties: We observe that we pause frequently or struggle to recall specific words also in contexts where we usually (or in the past) would not hesitate to speak fluently.

Grammatical Errors: We start making mistakes in syntax and morphology that previously were not an issue. Sometimes it looks like we speak (or write) with the structure, the matrix of another – more dominant – language in mind.

Code-Mixing: We start inserting words from the more dominant language when speaking, even if we are not tired, not in a rush, and when talking about familiar topics. This kind of code-mixing should not be misunderstood with the code-mixing in multilinguals during the early stages of learning another language.

Hesitation and Pauses: We make increasingly more effort in constructing sentences, formulating and expressing our thoughts and reasoning in the target language.

Accent Shift: We might sound “different” or have another accent whilst speaking the target language, which we didn’t have previously.

These signs can emerge in adults, children and even early bi/multilinguals who stop a particular language for a longer period of time.

Strategies to Prevent Language Attrition

Languages are like muscles. When we exercise regularly, i.e. use the languages on a regular basis, they will stay strong. Proactive strategies can help preserve fluency and keep the language retrievable at any moment.

Daily Interaction

Make sure to integrate the language into daily activities. For example:

- Use the language during meals, family gatherings or at specific moments during the day

- Assign specific topics or tasks to the language: storytelling, cooking, watching news and talking about them in the target language

Media Immersion

Consume authentic content in the target language.

- Listen to music or podcasts

- Read books, news articles, blogs, anything that motivates you in the target language

- Watch movies, shows, series, youtube videos

Community Engagement

Find or create a community of target language speakers – online and/or offline. You are welcome to join our private facebook group Multilingual Families, a vibrant and supportive community of multilinguals around the world. Find a local community of speakers and enroll in events like cultural festivals, or start activities for other families like yours.

Language Rituals and Games

Make language use a fun and entertaining family ritual or tradition.

- Designate moments or days where you intensify target language use as a family, e.g., Greek board game night, German Saturdays etc.

- Create challenges in the target language, like the ones we share in our Toolbox for Multilingual Families and on our youtube channel Activities for Multilingual Families.

Formal Learning Opportunities

What about taking courses about new topics to refresh or deepen your proficiency in the target language? This is very useful for refreshing or maintaining grammar, advanced vocabulary and maintaining the confidence of using the language in a broader variety of contexts.

The Role of Identity in Language Maintenance

Languages are deeply tied to our identities and sense of belonging (Oikonomidou, 2025; Limacher-Riebold 2018 and 2022). Losing a language can feel like losing a part of ourselves. Therefore, encouraging positive attitudes toward heritage languages is crucial to fully embrace multilingualism! Especially children benefit from understanding the cultural value of their languages through storytelling, cultural activities, and family history discussions (Garcia, 2009). These practices help to foster a strong connection between language and identity.

Several studies on language attrition highlight the importance of consistent use and emotional connection to maintain linguistic skills. Schmid & Köpke (2004) emphasize that the neural pathways weaken when the languages are not used regularly. However, they can be reactivated at any time through deliberate practice and exposure.

Fishman (1991) underscores the role of community efforts in maintaining minority languages, stressing that collective support is critical to preventing language shift, attrition and even loss. Community programs, language classes and cultural celebrations create environments where languages thrive.

For heritage language speakers, incomplete acquisition and learning, or early-stage attrition is common (Montrul, 2008). However, active engagement with the language can mitigate these effects. Revitalization efforts, both at home and in communities, can play a transformative role (Oikonomidou, 2025*). Reintroducing and fostering the use of a diminishing language involves intentional strategies, such as creating opportunities for active use in daily life and intergenerational transmission. Storytelling, traditional practices, and translanguaging approaches leverage the multilingual repertoire to bridge the gap between passive understanding (i.e. receptive language skills) and active use (García, 2009).

Language Shift, Attrition and Loss in Aging People

Aging individuals often experience changes in how they use and retain their languages. For multilingual individuals, these changes can lead to language shift, attrition and even loss, especially if certain languages are no longer actively used.

Older multilinguals may experience language attrition due to a combination of social, cognitive and environmental factors:

- Reduced Social Interaction: Retirement, relocation, or reduced social circles can limit opportunities to use certain languages, particularly if they are heritage or minority languages.

- Cognitive Changes: Natural age-related changes in memory and cognitive processing can make it harder to access less frequently used languages (Goral et al., 2007). Older multilinguals who maintain regular use of all their languages tend to experience less attrition and greater cognitive flexibility!

- Health Conditions: Neurological conditions like dementia or stroke can disproportionately affect one language over others, depending on which language networks are more robustly established and actively maintained (Paradis, 2004). Age-related language loss often affects the less dominant languages first, due to weaker neural connections. However, emotional and autobiographical memories tied to a language can enhance its resilience!

- Language Reduction in Communities: When older multilingual adults live in monolingual environments or are in touch with people who prioritize the dominant languages, they might gradually shift away from the other languages they learned.

Signs of Language Loss in Aging Individuals

- Difficulty Retrieving Words or Switching Languages: Older adults may pause more frequently or struggle to recall specific vocabulary, especially in lesser-used languages.

- Dominance of One Language: One language – often the more dominant, societal language – may start replacing others in daily use, even in contexts where the other languages were previously used.

- Incomplete Sentences: Sentences in the minority or “weaker” language may become simpler or grammatically inconsistent.

- Emotional Reactions: Frustration or withdrawal from conversations in weaker languages can signal discomfort with perceived “loss of fluency”.

Emotional connections to languages can sometimes lead to their preservation in surprising ways. For example, older multilingual adults with dementia often revert to their first language or earlier learned language, even after decades of not using it.

How to Support Aging Multilinguals

- Foster opportunities for Language Use: Encourage them to engage with their heritage or less used languages through storytelling, community events, or conversations with family. Multilingualism in aging individuals can serve as a cognitive reserve, delaying symptoms of dementia by keeping neural pathways active (De Bot & Makoni, 2005).

- Use Multimedia Tools: Introduce podcasts, audiobooks, or subscribed films in less-used languages to stimulate cognitive and linguistic pathways. Make sure to provide opportunities to talk about what they have listened to.

- Create Multilingual Routines: Establish simple habits, like dedicating specific times or activities to each language (e.g. using heritage language during family meals or outings, when talking about specific topics etc.).

- Leverage Emotionally Meaningful Contexts: Discuss memories, traditions, or cultural practices in the heritage language in order to create positive associations and preserve fluency.

- Bridge the Language with Fond Memories: When recalling fond memories, try to link them to the use of a target language. It is surprising to see how a specific memory can trigger the use of a language that seemed to be forgotten. In some cases, songs can ease the way back to the target language.

As our parents, grandparents and community elders navigate aging, nurturing their multilingualism can not only preserve their heritage but also support their cognitive and emotional well-being! Encourage active language use in meaningful contexts, i.e. in contexts where the use of the target language evokes positive and motivating memories. This will benefit the individuals and strengthen intergenerational ties.

Some personal experiences from members of our Facebook Group and suggestions on what to add to our list from followers on Instagram (Multilingual Families)

When we published a post about this topic on our facebook group, we also asked members to share their experience with us (in no particular order)**:

Zoe Stam: “I find my brain has a language limit. I used to speak decent Portuguese alongside English and French. When I started to learn Dutch I lost Portuguese which was the last learned language. I’d love to learn Spanish but I’m worried it will push something else out.”

Raffaella Scarpa: “I learnt Japanese when I was 22-25, even spent one year there. Sure, it wasn’t perfect but okay conversational level. After coming back I started doing my masters, started working and after some years… it was completely gone… Then of course I lost Spanish a bit when focusing on German because we were living there… Lost a lot of German now. But with Japanese it is really impressive how I literally don’t remember a single word!” (…) “I think the main reason it happened is that I never needed it again. No one to talk with. At the same time in my life I had a lot to focus on (studying, finding a job, house…). Then I had to learn a new language fast when we moved to Germany and that was probably the final step in abandoning it completely. Even now I wouldn’t have any motivation… so I don’t even try to watch movies or anything.”

Frances Dorrestein: “This happened to me with the smattering of Hindi I had from living in India. (…) I lived in Delhi for four years. What I have lost is fluency. I remember words but can’t make sentences. It was limited to begin with and now it’s gone. Same with comprehension. I pick out odd words but lose the overall meaning. Like regression to a baby’s first words stage!”

Agnieszka Wegner: “It happens to me, however the advice to practice daily is not practical for people who speak 5-6 languages, because they would need to practice them 5-6 hours a day. There is another possibility which I call “activation”. So when I know in advance I would need the “deactivated” language, I keep on listening to podcasts daily in this language. After a couple of weeks, it is quite ok to use it. When I was young and I had more free time to do “activation”, I would read a book to deactivate.”

J.S.: “I have varying experiences of this between the languages I have used throughout my life. My partner too, who is anxious about his lack of ability to find words in the native Limburger Dutch of his childhood with his few remaining relatives who still speak it, and his slightly fading German after being a German teacher for years.”

@leskidskalam suggested to add to the list of reasons that contribute to language shift, attrition and loss: “Lack of, or weak value associated to the language (emotional, social, cultural, etc.)”

Keep your languages alive!

Preserving and nurturing languages in multilingual families – or communities – does not happen by chance. It requires intentional and conscious effort. Simple, consistent actions, like regular family conversations or shared activities, can create a lasting impact, ensuring these languages thrive for future generations.

As multilinguals, we have the incredible opportunity to sustain the languages that root us in our heritage, strengthen bonds with our children, and unlock new possibilities for them and ourselves.

What is your experience with language shift, attrition and loss?

What are you doing to keep your languages alive ?

Please share with us in the comments!

*This is not code-switching, which is a similar phenomenon that occurs when we switch from one language to the other in the same conversation.

**I have the explicit consent of the facebook members to share their quotes and names or initials.

References:

De Bot, K., Makoni, S. (2006). Language and Aging in Multilingual Contexts. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Fishman, J. A. (1991). Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Garcia, O. (2009). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Language in Society 42(03), 344-345.

Goral, M., Levy, E.S., Ober, L.K. (2007). “Languages in the Aging Brain: A Lifespan Perspective”. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 144-162.

Limacher-Riebold, U. (12 May 2018). The Third Language Model. Multilingual-Families.com. https://multilingual-families.com/the-third-language-model/

Limacher-Riebold, U. (1 December 2022). From Cultural Identity Model to Language Identity Model. Multilingual-Families.com. https://multilingual-families.com/from-cultural-identity-model-to-language-identity-model/

Limacher-Riebold, U. (9 May 2023). The Dominant Language Constellation Model to visualize our use of multiple languages. Multilingual-Families.com. https://multilingual-families.com/the-dominant-language-constellation-model-to-visualize-our-use-of-multiple-languages/

Montrul, S. (2008). Incomplete Acquisition in Bilingualism: Re-examining the Age Factor. Studies in Bilingualism, 39.

Oikonomidou, Ch. (8 January 2025*). Dialects at Risk: Arvanitika Through the Eyes of a High School Student. https://multilingual-families.com/dialects-at-risk-arvanitika-through-the-eyes-of-a-high-school-student/

Oikonomidou, Ch. (1 April 2025). How to Help Multilingual Children Feel Proud of Their Language and Identity, Multilingual-Families.com. https://multilingual-families.com/how-to-help-multilingual-children-feel-proud-of-their-language-and-identity/

Paradis, M. (2004). A Neurolinguistic Theory of Bilingualism. Amsterdam : John Benjamins.

Schmid, M. S., Köpke, B., Keijzer, M., Weilemar, L. (2004). First Language Attrition: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Methodological Issues.

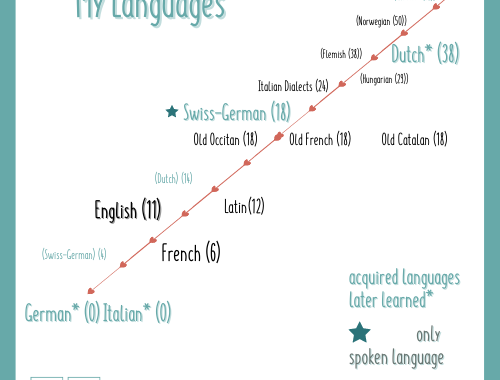

Ute Limacher-Riebold

Ute Limacher-Riebold, PhD, is the founder of Multilingual-Families.com and Owner of Ute’s International Lounge & Academy.

She empowers internationals to maintain their languages and cultures effectively while embracing new ones whilst living “abroad”.

She grew up with multiple languages, holds a PhD in Romance Studies and has worked as an Assistant Professor at the University of Zurich (Department of Italian Historical Linguistics). She taught Italian historical linguistics, researched Italian dialects and minority languages, and contributed to and led various academic projects.

Driven by her passion for successful language development and maintenance, and personal experiences with language shifts, Ute supports multilingual families worldwide in nurturing their languages and cultural identities in the most effective and healthy way.