First things first: What is CLIL?

CLIL stands for Content and Language Integrated Learning.

In very simple words, CLIL means learning a language by using it to learn something else. So instead of approaching language teaching like this: “Open your books. Now we learn grammar”, CLIL invites children to learn history, science, stories, games, and projects in the target language.

Children speak the language in order to play, collaborate, solve problems, and explore ideas. They hear and use the language because they need it. They are not “studying” the language all the time, they are using it naturally, as a tool for communication and learning.

Heritage Language Learning: A Teacher’s View

As a heritage language teacher teaching Greek to children of Greek origin growing up in Denmark, from the very beginning I never viewed my role as that of “just” a Greek language teacher. In heritage language settings, teachers often become a key point of reference for what the language, the culture, and the country of origin represent, playing a vital role in shaping how children relate not only to the language itself, but also to their background and sense of belonging.

This understanding shaped my pedagogical approach from the outset: teaching Greek was not only about grammar instruction and language exercises, but about engaging with cultural references, as well as elements of history and geography. Language learning, therefore, became a process of exploring identity through content, rather than an isolated linguistic goal.

Within this framework, CLIL offered a useful theoretical lens. It provided a way to describe an approach in which language, content, cognition, and culture are inherently interconnected. However, the focus was never on applying CLIL as a fixed method, but on responding to the broader educational and emotional needs of multilingual heritage learners.

It is also important to consider that CLIL tends to function particularly well in contexts where learners have already been introduced to the target language. In heritage language education, children rarely approach the language as complete beginners; they often possess receptive skills, familiar vocabulary, or lived experiences connected to the language through family and community. This existing exposure allows the language to be used meaningfully from the outset, which makes content-based approaches both pedagogically appropriate and emotionally accessible.

Engagement: Why It Matters in Heritage Language Education

When concerns are raised that a reduced focus on explicit grammar instruction may compromise language learning, it is worth considering a different and often more significant risk: the possibility that children may ultimately disengage from the heritage language altogether. When learning becomes disconnected from enjoyment, meaning, and identity, children may gradually develop negative associations with the language and, over time, choose to abandon it once they are able to make that decision independently. In heritage language contexts, this risk is particularly pronounced.

One of the most critical indicators of success in heritage language education is whether children choose to continue. Unlike compulsory schooling, heritage language programmes mostly operate as after-school activities, where motivation, enjoyment, and emotional safety are essential conditions for sustained participation.

Within this context, CLIL-informed approaches can support engagement by framing language learning as interesting, relevant, and socially meaningful. When children experience the heritage language as a tool for interaction, creativity, and shared discovery, they are more likely to use it spontaneously and to associate it with positive learning experiences.

Research in heritage language education and sociocultural approaches to language learning consistently highlights the close relationship between meaningful language use, emotional engagement, and identity development. Heritage languages are deeply connected to family relationships, cultural belonging, and self-perception. When learning environments fail to support these dimensions, children may distance themselves from the language; conversely, when language learning is meaningful and affirming, it can strengthen a child’s relationship with both the language and the cultural worlds connected to it.

In this sense, heritage language schools and community-based educational spaces play a vital role. They are not simply places where a language is taught, but environments where multilingual children can explore, negotiate, and embrace aspects of their identity in a supportive setting. When heritage language programmes are reduced to grammar-driven instruction alone, we risk teaching children that their heritage language is something to endure rather than something to claim and be proud of.

Is CLIL a realistic solution for heritage language education as it exists today?

Field-based data from an international survey conducted in collaboration with Paidokipos Børneklub, the Heraklion Directorate of Primary Education (Greece), Ute’s International Lounge (Netherlands), and the Greek Language Department of Ghent (Belgium) (2024) highlight the structural challenges faced by Greek heritage language educators abroad. Many report limited access to appropriate and modern teaching materials, minimal institutional support, and insufficient training opportunities. These conditions strongly influence what educators can realistically implement in their everyday practice.

CLIL-informed approaches require time, careful planning, pedagogical autonomy, and opportunities for collaboration. Behind a single CLIL lesson, educators may invest hours of preparation. When ready-made materials are scarce and professional networks are weak or fragmented, the responsibility falls almost entirely on individual teachers.

Under these conditions, expecting educators to systematically apply CLIL without structural support risks placing an unsustainable burden on those working in heritage language settings, many of which operate as after-school or community-based programmes.

At the same time, the core principles of CLIL remain highly relevant. When applied flexibly and realistically, they can inform practices that support not only language development, but also motivation, identity, and long-term engagement.

To conclude with a wish: the discussion should not focus solely on whether heritage language teachers “use CLIL” or not. Instead, it should address how heritage language education can be better supported, resourced, and valued, so that educators are able to create learning environments where children do not simply learn a language, but learn to connect with a part of who they are.

References

Cummins, J. (2001). Bilingual children’s mother tongue: Why is it important for education? Toronto: OISE, University of Toronto.

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation (2nd ed.). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Paidokipos Børneklub, Heraklion Directorate of Primary Education, Ute’s International Lounge, & Greek Language Department of Ghent. (2024). Voices of the diaspora: International survey on Greek language education for children abroad.

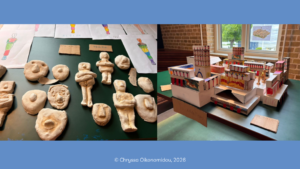

Chryssa Oikonomidou

Chryssa Oikonomidou is the Co-Founder of Multilingual-Families.com and Founder of Paidokipos, a creative Greek teacher, storyteller, and animator of interactive educational theater events. With a background as Senior Executive, she leverages over a decade of experience across various sectors to enhance her work in education, bolstered by her studies in education and multilingualism. Having not enjoyed school as a child and inspired by her two bilingual children, she is determined to make her lessons engaging and enjoyable for her students. She combines her diverse skills in didactics and project management to foster a rich educational landscape for young learners.